AI Conference at Chang'an University - Key Insights

Summary of the Conference

The 8th Translation Industry High-End Forum and Academic Seminar on Translation Change and Innovation in the Era of Artificial Intelligence was held in Xi’an, China, from October 25th to October 27th. I delivered a keynote speech titled “Localization in the AI Era: A Professional Perspective.”

The Sociogram and the Technogram

Dr. Minhui Xu, an Associate Professor at the University of Macao, presented on “The Transformed Translators’ Roles in the Era of Digitalized Translation: A Sociological Perspective.” Her talk sparked a significant realization for me.

Dr. Xu referenced Bruno Latour’s 1984 Actor-Network Theory, which conceptualizes human actors as part of the “sociogram” and non-human actors as part of the “technogram.” Human actors overcome limitations in the technogram, while non-human actors address limitations in the sociogram.

This framework provides a valuable perspective for understanding the transformations occurring in the translation and localization industry during the AI era. Before AI, the technogram was relatively static, only enhancing its capabilities when updated by human actors. However, AI is evolving into a dynamically self-improving non-human entity. It addresses a primary frustration of translators: “the system doesn’t learn from my actions.” With adaptive machine translation, fine-tuning, and prompting, AI demonstrates the ability to learn from human actions, dynamically overcoming limitations in the sociogram.

The realization of AI’s capabilities is leading to a widespread slowdown in traditional language services. CSA Research notes that 2023 marked the year of “Peak Localization,” with traditional language services expected to decline. My wife, who works with content and AI at Duolingo, has observed several rounds of contractor layoffs. Those who once relied on their unique competitive advantage in content creation and translation are now finding AI to be a formidable competitor. Nearly all translators have upskilled and rebranded as machine translation post-editors. If you can’t beat it, join it.

As AI demonstrates its ability to dynamically overcome limitations in the sociogram, humans are striving to identify new limitations in the technogram. Is there anything that AI cannot do?

Dr. Xu shared an insightful quote from AI ethicist John Danaher (2022): “A lot of the contemporary debate about automation is misguided because it is impossible to automate work; it is only possible to automate work-related tasks.” I find this mantra compelling. Danaher defines work narrowly as an activity performed for economic reward. The availability of that economic reward depends on the desires and values of the people in an economy directing capital, and those desires and values are constantly evolving.

The agricultural revolution largely automated the production of food as a commodity, whereas previously, food was acquired through hunting and gathering. This shift was accompanied by a change in the values and desires of early humans, who began to increasingly value more abstract and high-level expressions, such as art, culture, and social structures. The focus shifted from mere survival to the pursuit of intellectual and cultural advancements. Similarly, in the AI era, humans are updating and upgrading the things they value.

Human aspirations, and the work required to achieve them, remain beyond the reach of AI. Elon Musk cannot ask ChatGPT how to get to Mars. Granted, AI’s impact is growing from the ground up. Consider all the automation and AI involved in manufacturing such rockets. Whereas humans once aspired to formulate black powder, now we aspire to build rockets to take us to Mars. Human work is downstream from human aspirations, and those aspirations are always ascending.

Linguists facing competition from AI should remember that translation is always done with a purpose: to communicate, to convince, or to inspire. These purposes often serve as intermediaries for economic aims, such as selling a product or gaining an economic edge. In other words, capital is directed toward translation to achieve a purpose. Although AI is proving to be a capable competitor in translation and content creation, it cannot yet perform some tasks crucial to the overall purpose.

A prime example of this is when I was asked to teach an intercultural communication seminar to employees of SINOSURE, China’s state-owned credit and export insurance company. The week’s activities focused on communication in its main forms: speaking, writing, and presenting. Although writing is important, I spent surprisingly little time on its mechanics. Instead, I emphasized principles of building trust when communicating with non-Chinese.

The participants of this training regularly travel abroad to sign multi-billion dollar deals insuring payment for Chinese goods sold internationally. International negotiations are not conducted by robots; they require a human with a firm handshake, a confident disposition, and cultural finesse. Linguists seeking to re-skill and strengthen their position against AI encroachments can step into the role of cultural consultants, training global business and government leaders to communicate effectively across cultural barriers.

LangOps is the new face of localization

My talk focused on LangOps as the face of localization in the AI era. With AI driving much of the language services, data and AI assume a more significant role. However, integrating everything requires forethought and strategy. That’s where LangOps comes in, as the overarching vision for implementing an AI-first, data-centric, human-at-the-core localization program. Enterprises and localization suppliers are now paying extra attention to their data pipelines and AI capabilities, pushing operations toward higher efficiency and more consistent quality.

Chang’an University

I extend my gratitude to Ruying from Chang’an University, who arranged my travel and accommodations. She was a well-organized, prompt, and hospitable host. She introduced Chang’an University as one of the top universities in China for automotive and highway construction technology. She teaches English to Chinese students who graduate to work for Chinese vehicle manufacturers and construction companies abroad.

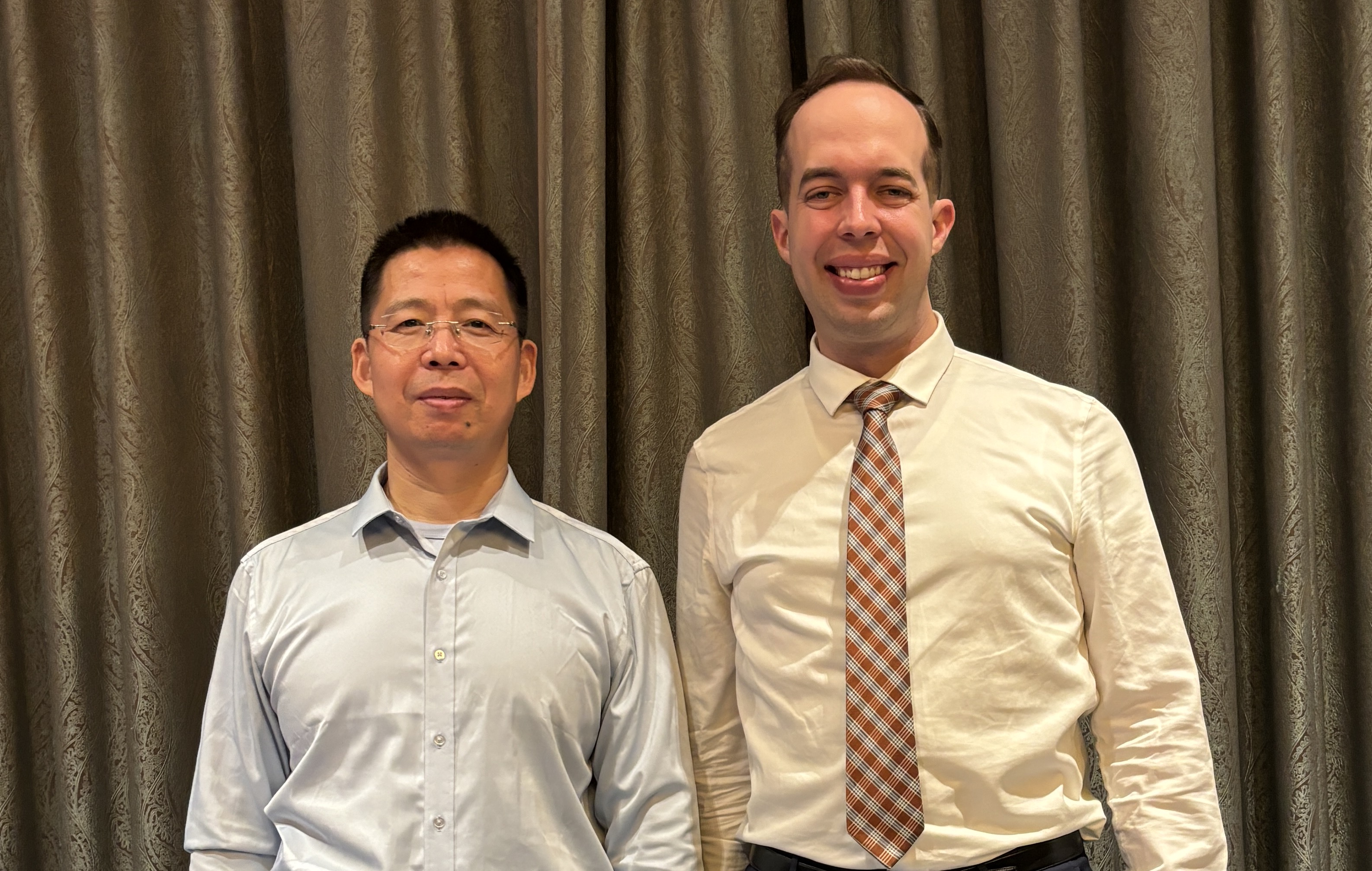

Professor Sun Sanjun

I am grateful to Professor Sun Sanjun from Beijing Foreign Studies University for inviting me to this conference. He delivered an enlightening presentation on the quality evaluation of neural machine translation and large language models. He is the editor of a book to which I am contributing a chapter titled “Localization in the AI Era.” The book will be published by Routledge later this year.

Professor Habibe

During my lecture, I mentioned that I speak Russian and a little Uzbek. Afterward, a foreign-looking woman approached me and began speaking Uzbek—or so I thought! I could only understand about 50% of what she was saying. She introduced herself as Habibe, a professor of translation at Xinjiang University. She had heard from my presentation that I speak a little Uzbek and came to introduce herself using Uyghur, her mother tongue. She has been involved in translating many works of literature, film, and TV into Uyghur.

She explained that the mutual intelligibility between Uzbek and Uyghur should qualify them as dialects of the same language. Consider Mandarin and Cantonese, which are considered dialects of Chinese and yet are not mutually intelligible. Uzbek and Uyghur are indeed mutually intelligible, but for reasons known only to linguistic anthropologists, they are considered separate languages. Some experts believe that Uzbek, Uyghur, and other Central Asian languages are more accurately conceptualized as dialects of a Central Asian Turkic language.